A decade before the French Minister of Cultural Affairs, André Malraux, published Musée Imaginaire, often translated into English as Museum Without Walls, the itinerant French grand-père of conceptual art, Marcel Duchamp, began production on his “Boîte-en-valise”. “Everything important that I have done”, he wrote, “can be put into a little suitcase.” Between 1935 and 1940 – latterly negotiating German-occupied Europe – Duchamp compiled lists of his artworks and their owners, took trips to note characteristics and sourced manufacturers who might help him realize these most important works in miniature, to be contained within a brown leather valise.

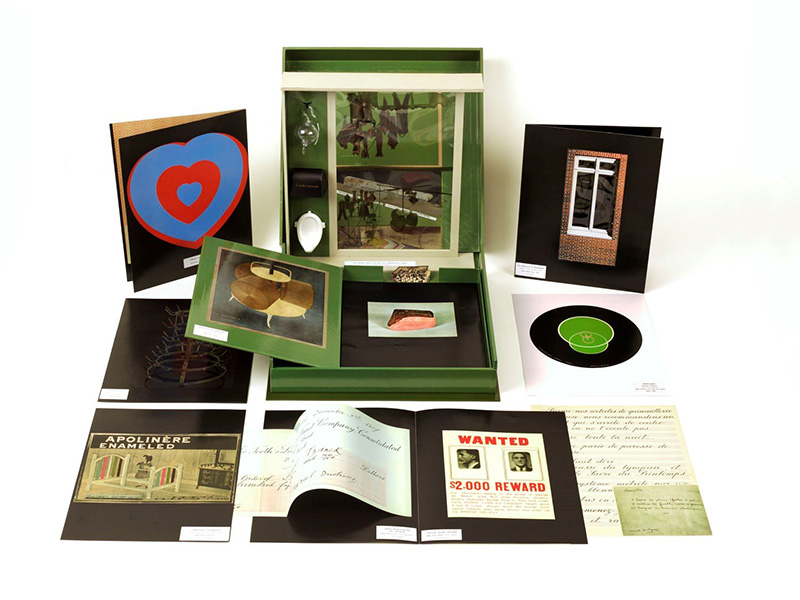

As Malraux diagnosed the circulation of artwork far beyond the museum in art books, postcards and posters, Duchamp was wryly reinstating the museum in mobile Lilliputian terms. If Duchamp’s sovereign “Fountain” (1917) urges the spectator to ask “what is art?”, “Boîte” asks the question “what is the museum?” Sometimes referred to by Duchamp as an “album” and at other times a “book”, “Boîte-en-valise” is translated as both “Museum in a Box” and “Portable Museum”. This doubling is echoed in the work’s attribution “from or by” Marcel Duchamp or Rrose Sélavy, Duchamp’s female alter ego.

Duchamp hoped to produce “Boîte-en- valise” in a series of 300 but only achieved twenty when he packed his suitcases and emigrated to the US in 1942. Throughout the 1950s, until his death in France in 1968, he produced different series of editions, each an iteration of works enclosed by different coloured fabric cases. Series A, that initial edition of twenty, were the only ones contained in a leather valise; last year at Christie’s, New York, one realized an auction price of $2,965,000.

The contemporary French artist Mathieu Mercier’s collaboration with Association Marcel Duchamp on the reissue of a Series G Museum in a Box of 1968 is an opportunity to own an important piece of modernist art. Duchamp, ever the entrepreneur, would have approved. Since this reissue’s keenly anticipated release, delayed by several months due to production difficulties, I’ve seen punters buy three at a time in my local bookshop. Printed in an edition of 1,500, they have already doubled in price on Amazon.

Opening the box – ever so carefully, so as not to compromise its resale value – is to reveal an architectonic interior akin to a doll’s house. It is the doll’s house, Susan Stewart observed in On Longing (1984), that promises “an infinitely profound interiority” that transcends everyday time. I played with it once, closed the lid and put it away under the bed. I await the profound machinations of the art market to make it transcend what I paid for it so I might pack my suitcase and emigrate.