Unwittingly enacting something central to Edward Thomasson’s exhibition “Other People,” I reflexively supplemented its title to constitute Jean-Paul Sartre’s familiar aphorism “Hell is . . .” Abstracted from its context, the line has become the meme-like slogan of misanthropes. Its separatist ideal, latently theological, envisions withdrawal into the self, the logical consequence of which is loss of intimacy or empathy.

This is inimical to Sartre’s philosophy of le regard: that we are dependent on and qualified by the Other. To be seen, Sartre writes, is to be “the instrument of possibilities which are not my possibilities,” to be constituted “as a means to ends of which I am ignorant.” If this enables actions it also prohibits them, representing a limit to freedom that Sartre goes so far as to characterize as slavery. If Sartre’s philosophy of relation was founded on the disembodied specular image, Thomasson’s exhibition of five watercolors and a video spotlit that philosophy’s codependence upon the body.

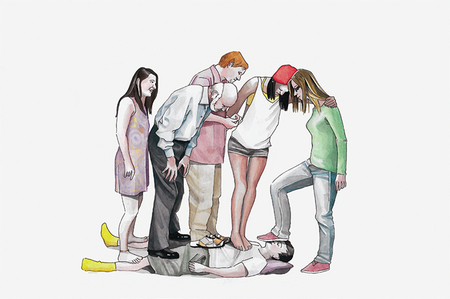

The video installation Pressure and the five untitled works on paper in “Other People” (all works 2016) shared a visual style that mimics a kind of institutional neutrality. Culturally specific, it evokes British National Health Service infographics or Charles Raymond’s illustrations for The Joy of Sex (1972), each concerned in their way with relation and care. In one drawing, three pairs of young men at different stages of foreplay line a couch: This might be group sex if the couples weren’t so peculiarly oblivious to each other. In another, three office workers victoriously surmount two heaped piles of people and a man on all fours; this might be a corporate team-building exercise, but the weight of all the bodies would crush those at the bottom. In a third, a key to the video upstairs, a man in yellow socks lies flat on his back, arms at his sides, as four cheerful men and women of varying ages stand, balanced, along the length of his body. At his head, a woman plants her foot in his face. Masochism or therapy? What’s the difference? Everyone appears gratified.

Upstairs, as if the aftermath of a breakout group, chairs were stacked and placed haphazardly in front of the video, which uses the set, actors, and music from Thomasson’s play Volunteers, performed at the David Roberts Art Foundation last April; it explores how the dynamics of male and female protagonists’ interpersonal relationships with others outside of work finds expression in their collegial relationship as manager and employee in the office. Cut with rhythmic and formal precision, the video moves between the female protagonist and friend volunteering as bodies for a masseur’s instructional class; the male protagonist’s fetishistic servitude to a man who makes him fetch drinks on all fours before balancing on his back; and, in the office, the manager spouting obfuscatory jargon to an employee about a “five-minute favor scheme.”

Voice-over grants insight into the employee’s thoughts, who gazes out at us, the viewer: “There are times you feel like you’re being used, but I’ll take that over being in someone’s debt any day.” Perhaps that’s why she agrees to work for free on her manager’s scheme? “I want you to know I have your back,” he tells her. “I don’t want you to have my back, I have my own back,” she retorts in voice-over. As she drops on all fours to pick up folders he’s too busy to move, she resembles him in the episode in which he subserviently fetched drinks, blissfully giving for his own sexual gratification. Figuratively speaking, he “has her back,” just as, Thomasson implies, his partner has his back when he stands on it. Throughout the film, between these three scenarios, the artist masterfully teases out the poetic valences of this colloquialism, along with images of pressure and balance as forces in codependent relations. He transforms simple language and images into metaphors of moving complexity. Receiving is also giving, being used is also using, and being owed is also to owe. Flickering between self and other, “Other People” reminded one of the ways in which art is an empathy machine.