It’s been a baffling week. But then when is it not? On Friday evening my friends (lesbians, feminists too) and I joined a memorial service at King’s College Chapel on the Strand to commemorate what would have been Derek Jarman’s 72nd birthday. Gilded twin arches of the George Gilbert Scott interior framed a bed sheet suspended centrally in the transept. Emerging from the twilight a creased sheet – splayed open, a poignant image of vulnerability – bore a projection of Jarman’s old-fashioned signature, and later a 24-hour looped screening of his 1985 film The Angelic Conversation.

To further frame the screening, artist Neil Barlett was joined by Simon Watney, a tireless AIDS activist and art historian, to remember Jarman. The creased sheet belonged to Barlett: in the late ’80s, as ‘Mistress of Ceremonies’ of the National Review of Live Art in Glasgow, Barlett commissioned a new work by Jarman. They discussed the project on the phone, before Jarman threw himself into the project with typical vitality. In the centre of the gallery space, Jarman displayed a bed zoned off by barbed wire; tarred mattresses edged the gallery walls; on an unmade bed (made between, of course, Yoko Ono’s and John Lennon’s bed-in and Tracey Emin’s un-made bed) young gay men – and apparently Tilda Swinton – took it in turn to lounge among the paraphernalia of gay sex, such as KY jelly, poppers, and so on. Watney – whose absence from New Year’s Honours lists and lack, even, of academic tenure is egregiously symptomatic of Britain’s attitude to its intellectuals – was here because, among other reasons, he publicly defended Jarman when the tabloids peddled ‘plague’ trash and divine retribution for ‘homosexuality’. In the late ’80s, with friends dying in his wake, Watney shuttled back and forth between London and New York to learn newest developments in HIV and AIDS medicine. Watney met Jarman back in the ‘70s. They shared a love for Elizabethan houses, as well as London’s churches and museums. He was, Watney told us, a reliable sounding board for Jarman to test feature film ideas. When Jarman laid dying of AIDS-related illness in St Bart’s Hospital, Watney would read quietly to this husk of a man. Barlett’s and Watney’s remembrances were, frustratingly, only glancing, necessarily limited to the hour before the 7pm screening. Watney repeated the same (no less affecting) familiar stories. A few particular comments lodged in my mind.

Had Derek been alive, many of us, Barlett noted, would be partying, drinking, dancing and listening to his gregarious stories. Jarman was outlived by many of his contemporaries. Consequently, audiences at Jarman exhibitions, screenings and events in London are attended by many who knew him: it’s a fascinating glimpse at living history. (‘When you reach 50,’ Barlett said to Watney in their conversation, ‘you become history’.) Yet, increasingly, such events are curiously divided, between those who knew him personally, and younger people who, although may not have not met him, feel tremendous affection for, ownership of, this public figure. At the recent opening of the exhibition of Jarman’s notebooks, also at King’s College, this older generation looked confused by youth’s presence. (I recently experienced something like the paranoiac reproach of the older generation when I wrote about Jarman’s paintings for Wilkinson Gallery late last year. After all, I reasoned with the commissioner, others still alive who knew him could do it, others who were also gay: the great learning from Watney is the violence of speaking for others; from Jarman it’s the vital importance of speaking for oneself.)

In Scott’s chapel, the old familiar intergenerational rift rose again. We must remember, we must not forget our struggles of the 1980s, our history, Barlett insisted. That much I agree with. But when he we went on to say the following I couldn’t help feeling – well – alienated and condescended to (I paraphrase): ‘One thing that annoys me about my students is that they think the ’80s was so glamorous. It wasn’t. It was horrible. We were victimized all the time. They also envy how we knew who the enemy was, whereas they don’t today.’

Not to mention the silencing of absent students who couldn’t speak for themselves, why deny the distortions of nostalgia, distortions that might lead to deeper understanding? No one who wasn’t there can get it right all the time, but at least give us a chance. Allow us to learn from the past in order to understand our present and move forward. This over-vigilant gatekeeping carries internecine effects.

At the end of the conversation, Watney read two very moving texts. The first was the last poem he read to Jarman before his death; the second was Tory legislation on the policing of mobility for Romanians seeking asylum in the UK: those with Hep B and those HIV+ – ‘That’s me,’ Barlett said of the former; ‘That’s me,’ Watney said of the latter – would automatically not be granted asylum. The legislation, by isolating what the two men agreed were gay diseases, evidenced continued prejudice against gays.

On the Sunday of the same weekend – shortly after, I suppose, The Angelic Conversation looped itself out on the Strand – I walked to the Chisenhale Gallery in East London for the last day of New York artist Jordan Wolfson’s video installation ‘Raspberry Poser’. At the desk I was instructed to leave my shoes at the gallery door before entering. For some reason separation from my shoes always causes me some anxiety. Besides, my socks, wet from the dew of Victoria Park, looked sweaty and smelly. Perhaps I was immune to their smell? I felt vulnerable.

Beyoncé’s song Sweet Dreams blasted at half-speed as I passed through the double row of black-out curtains, forcefully engulfing me as I continued into the gallery. Inside, a cream pile carpet covered the floor. A vast suspended screen – an image of excess – on which Wolfson’s film was projected, bisected the gallery, illuminating a viewing area in front, while casting the empty space behind into darkness. All around bodies reclined and luxuriated in front of the screen, transforming the gallery into some kind of gigantic home cinema set-up. Sweet Dreams’s pitch-shift lent Beyoncé a demonic male voice and drew attention to the lyrics. ‘You could be a sweet dream or a beautiful nightmare either way I don’t want to wake up from you …’, sings B, accompanied by distant restrains of ‘Come alive’. Animations, of course, do come alive, and the intoxicated refusal to wake, whatever may come, is emblematic of the kinds of mad trysts we experience everyday in various ways. Sweet Dreams has a dark, mesmerizing power. When this was followed by Sweet Dreams played out at normal speed it made me want to dance, it made me want to run outside, thrust my arms out, vogue, and shake my hips – exactly the effect it has when when I hear it in a nightclub. Its affective power – or whatever the expression is – couldn’t be contained by Wolfson’s framing of it in this installation. I watched it four times. After I’d ceased feeling giddy about Sweet Dreams I began concentrating on the images.

A cartoon boy self-eviscerates while returning the gaze; several times he literally cuts himself open to neatly unpack his entrails, like those schematized medical models. This cartoon boy unpacks his body augmented into ‘actual’ shots of sunny street scenes of SoHo in New York. Urbane, cosmopolitan, wealthy, sexy, confident, knowing SoHo. Formerly marginal SoHo. In a plush anonymous hallway, the boy contorts backwards and begins strangling himself. The strangling causes his body to concertina outward from the waist, describing a growing arc. Then he speaks – the only dialogue in the entire work: ‘Are you rich?’ the boy asks. ‘Yes,’ comes his response in a different voice. ‘Are you homosexual?’ he asks. ‘No,’ comes his response, again in a different voice. Is this Wolfson’s voice? Is it the assumed voice of us, the viewer, pruriently speculating on Wolfson? Perhaps this, the only dialogue, concedes that it’s easier to admit to being rich than it is to being ‘homosexual’?

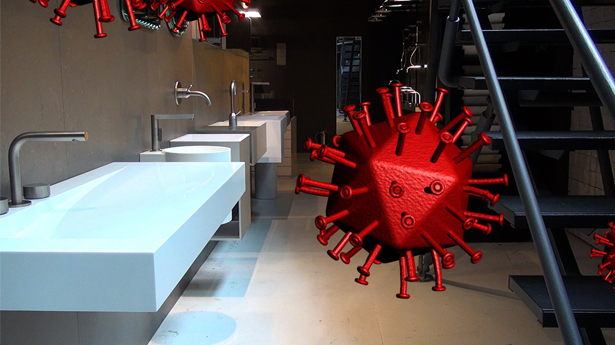

Sunny SoHo scenes are augmented too by wafting condoms filled with a fluid consisting of small hearts. Animated HIV virus cells bounce whimsically in unison on yuppy apartment sofas. As I watched I imagined a certain idiotic art director I know who would see in Wolfson’s work a fresh look – fresh looks are what fashion people who spend thousands of pounds on books just for the pictures want. With this visual style, I thought, Wolfson could even direct a music video. At a certain point we join a punk, with severe skinhead, ‘Iggy Pop’ Tippex’d on his leather jacket lapels and spiky Doc Martens, wandering through Paris (it evokes the disaffected youth of Robert Bresson’s L’Argent, 1983). The punk performs disconnection and alienation. He drifts in reverie, running his hand along walls in naive wonderment. He squats in flower beds. Is he a sad punk? He eats a salad in an outdoor seating area – one of those sparse rip-off tourist trap salads that costs €20. Is he a rich punk? Is he even a punk? Towards the end of the loop is a low, sidewards shot of the punk squat on a lawn with his trousers down; he bares his naked, prone arse high in the air. I think of Courbet’s Origin of the World, queered. A non sequitur. Slowly, inevitably, the shot zooms towards his arse and I find myself thinking of Leo Bersani’s ‘Is the Rectum a Grave?’ (1987). A foundational text, written by a gay scholar, on gay promiscuity, promiscuity, Bersani observes, in spite of the HIV virus.

At the end of Raspberry Poser, the sad punk smiles, looks to the side of the camera, then meets its gaze directly, in effect returning our gaze. The punk – for the sake of giving it a name – smiles. The only other who has returned our gaze is the animated boy who can’t help self-eviscerate.

The punk, to give him his proper name, is Jordan Wolfson. Wolfson is mindful of flirting with a gay aesthetic. In Interview magazine recently the sculptor Helen Marten observed how his series of lobster claws adorned with hardcore gay porn are emptied of tactile pleasure. ‘I’m just making these things,’ Wolfson replies. ‘But it’s funny because people will assume that I’m gay or that I’m secretly gay’. Eddie Peake is another artist, among others, who, similarly, wants to act up this gay aesthetic. (Note here also Justin Bieber’s recent sporting of an ACT UP T-shirt – the same Bieber who believes Anne Frank would have been a ‘Beleiber’ had she not been murdered by Nazis.) In the Chisenhale’s press material Wolfson describes HIV as a poser. In the interview with Marten he characterises it as floating ‘joyfully around, spinning and expanding and contracting’ in Raspberry Poser. Actually this harbinger moves with insipid joylessness through now gentrified neighbourhoods that were once scenes of SoHo’s AIDs pandemic. Wolfson is not a punk, nor is he gay. So is what we see here some post-identity dispatch from New York? Are we in a post-identity, anything-goes world? Only three weeks ago, a young black feminist spoke on London radio about how it was never, ever acceptable for a white person to use the N-word, even if they love black music and have black friends. Before Christmas I argued – for the sake of argument – with a young lesbian critic who chided a straight male curator at the ICA, talking openly about a post-gay aesthetic. ‘Yeah,’ I goaded, ‘but isn’t this the fall-out from queer studies? The great lesson is that identities are never final. Besides, queer is not the exclusive reserve of the LGBT community. And art and the culture industry will instrumentalize it whoever objects.’ This curator was at the King’s College Jarman screening. One of my group of friends had arranged to meet her there. We were reintroduced and I apologized for being argumentative.

Are you rich? Yes. Are you homosexual? No. If Wolfson has anxieties about his own private wealth, his own tendency for posturing, his own megalomaniac neuroses, the legacy of the AIDS crisis should not be a vehicle for this.

With thanks to Laura E. Guy for discussing aspects of this article with me.