The only stateside photograph in Hattie Collins and Olivia Rose’s book This Is Grime flickers at the edge of abstraction. Illumined by camera flash, a hazy specter—the fug of weed smoke, maybe—renders the signage of Williamsburg’s Music Hall barely legible: DIZZEE RASCAL—BOY IN DA CORNER. The show took place this past May, and Dizzee, offered an undisclosed fee by the Red Bull Music Academy, had agreed to perform the entirety of his Mercury Prize–winning album Boy in da Corner (2003)—something he said he’d never do—in New York, no less.

With a sound that could only have emerged from the diasporic foment of London, Boy in da Corner offered everything there was to be known about postmillennial Britain’s capital city, an unremitting setting so potently conjured, thirteen years on, by This Is Grime. Punctuated with crackling paranoia and references to nihilistic violence, Boy in da Corner delivers social-realist observations, referring to drugs, teen pregnancy, racist policing, and the so-called “tough but fair” governance of Tony Blair’s New Labour party. Bow, where Dizzee was born and raised, is a district of the borough Tower Hamlets, which has long had one of the highest poverty rates in England and Wales. There, in the early 2000s, MCs not even old enough to enter nightclubs clashed in youth centers, and a teenage Dizzee produced tracks at school. His excoriating inner-city patois, set over Sinofuturist synth lines and ratchety beats, shredded the niceness of UK garage—all designer labels, desire, and champagne—that had been the sound of the streets before him.

In October, five months after Rose shot her enigmatic photograph in Williamsburg, Dizzee finally performed Boy in da Corner to a home crowd at the Copper Box Arena, a venue built as part of the widespread (and catastrophic) redevelopment of East London for the 2012 Olympics. The show reaffirmed Boy in da Corner’s status as one of grime’s first and most influential albums, one that provokes nostalgia but remains generative, too: Producers continue to sample and remix its tracks; young MCs pastiche lyrics and inhabit its quick-fire flows.

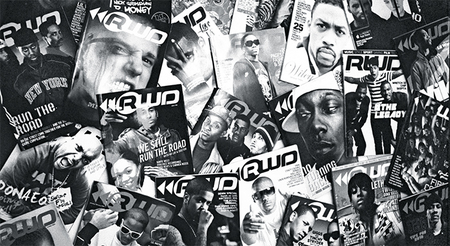

This past year, grime has begun to receive its due as the UK’s “most significant aural rebellion since punk,” as The Guardian recently described it in an editorial. The BBC broadcast a four-part documentary on the genre, and Tottenham-based MC Skepta won the Mercury Prize, beating David Bowie and Radiohead. Meanwhile, even a podcast commemorating the fortieth anniversary of London punk touched on grime, when writers Jon Savage and Laura “Hyperfrank” Brosnan agreed that each of these rebel genres—youthful, oppositional, naive at first—gave voice to their respective generations. But where punk’s favored technology of dissemination was the Xerox machine, grime had the glossy urban music-and-streetwear magazine RWD, MSN Messenger, and online forums. Punk was DIY; grime, Brosnan said, is “entrepreneurial.” (As twenty-year-old MC Novelist asserts in This Is Grime: “Fuck feds. I’m on all of that. But at the same time, I want to teach people how to govern your money.”)

Given its enterprising ethic, grime’s entry into the mainstream and its embrace of resulting commercial rewards come as little surprise. (Dizzee performed in front of the Queen at the 2012 London Olympics; Drake joined Skepta’s label, Boy Better Know, last year.) But it has also suffered the usual agonies that accompany a move into a wider cultural arena: As its origins, history, and meaning are being wrested from those who shaped it—now mostly in their early thirties, still active on the scene, and willing to talk—the ensuing scramble for narratives forms the context for Collins and Rose’s unambiguous declaration of identity in their book’s title. An oral history of sorts, the volume represents key protagonists alive and dead—MCs, producers, DJs, promoters, editors, writers. Their voices, slang and cadence intact, tell of a heterogeneous network of affiliations, friendships, and group identifications.

Rose’s black-and-white photographs, largely printed uncropped and full frame, signal their analog artistry in distinction to the ephemerality of Instagram. They’re cooler, more reflexive, than the fierce, flash-lit intimacy of Open Mic, photographer Ewen Spencer’s 2005 document of the East London scene. And Rose avoids the pretense to social documentary in Simon Wheatley’s Don’t Call Me Urban! The Time of Grime (2010), which pointed a camera at poverty both to build a brutal visual context for the music and to counter negative stereotypes of urbanity.

This Is Grime alternately serves as a style manual, a historical record—in the manner of Richard Barnes’s Mods! (1979) or Val Hennessy’s In the Gutter (1978)—and even something of a crystal ball. Speculations on the genre’s future near the book’s end seem trenchant given British prime minister Theresa May’s recent declaration, after the Brexit vote, that “if you believe you’re a citizen of the world, you’re a citizen of nowhere.” The creeping insular nationalism emblematized by Brexit—but not, of course, exclusive to Britain—is anathema to cultural emergence. Grime would be unimaginable without Britain’s Caribbean and African immigrants, and This Is Grime documents both a sense of shared purpose that perhaps emerged as communities resettled and recombined in new inner-city settings, and a concordant genre that Novelist, in the book, calls “an unorthodox, rebellious sound that represents madness from the hood, the street.”