I no longer remember how I related to Blackstreet’s exorbitant display of emotion in ‘Don’t Leave Me Girl’ when it charted in 1997. Between school and shooting hoops up the field, as an 11 year-old I spent as much time as humanly possible at either of two best friends’ houses, mainlining on Nickelodeon or MTV. This had its localised effects: at that age I imagined myself into music videos so, as well as reciting lyrics, I could mimic dance routines, and had specific gestures and affectations mastered that entered my daily life. Small towns like mine became Transatlantic intersections between cable-televisual African-American culture and tepid Cool Britannia.

‘Don’t Leave…’ belonged to a continuum, of sensitive, strong men displaying heartfelt sentiment (the year before, 2Pac rapped introspectively, in a white suit in heaven, over the same melody about lost friendships on ‘I ain’t mad at cha’), aggy-for-the-sake-of-it bearded geezers, and Girl Powered high kicks. If the Spice Girls felt new and affirmative it had little conscious effect on refashioning my relations with women (I credit others around me for that). I didn’t need Oasis’ emotional invalidity. But ‘Don’t Leave’… ‘Don’t Leave’ soundtracked all kinds of melodramatic fantasies of secret crushes announcing their departure, or me announcing my own. Its effect was entirely solipsistic. ‘Don’t Leave’ gave solace to – and simultaneously validated – the navel-gazing emotional clamour of my 11 year-old self (I despise that person, as I hope my 40 year-old self will my current 28 year-old self). It seems curious now, as with so much pop music, the generational separation between those consuming it and those making it.

I was reminded of all this towards the end of last year when the Catford-born producer Mr. Mitch preceded his acclaimed first LP, Parallel Memories, with the release of a four-track EP titled Don’t Leave. The eponymous first track, included on Parallel Memories, opens like Blackstreet’s track, as if from the middle, with the syncopated refrain: ‘if you take your love away from me I’ll go crazy, I’ll go insane.’ Except Mitch had pitched down the tempo, retaining the morphed key, like a Walkman just before the batteries drained. But the energy never fully drains. Minimal melodic progressions of bass and kick drum accent steady pitched-down loops of ‘don’t leave me girl’. Around it, a rapid, repetitious ditty flurries over layers of deteriorated plinks and sustained wavering tones. They rise and fall, with and against, in and out of one another.

Samples are portals to far-away times and places. I laboured over the context of my Blackstreet listening because it’s where I was first involuntarily transported when I heard Mitch’s ‘Don’t Leave’ in a Dalston club, as I suspect others were too, in their individual ways, of a generation with shared cable-televisual experiences. In the music press, consensus quickly grew that Mitch was grime’s most melancholy man. Masculine displays of emotion were confused with melancholy, melancholy with nostalgia. His music was labeled emo grime. Was he even making grime?

Someone’s always announcing grime’s death in some internet forum. In its own way, emo grime was understood as a death knell (some called it ‘white grime’ in spite of Mitch’s skin colour). 2014, yet another terminal year for grime’s short life, was also the year journos announced it’d never been more alive. What did become apparent last year was that for the first time the genre had become fully self-referential, with new producers recycling early grime productions, or signature characteristics, in order to make new material. That, Mr. Mitch explained to me, was something that had never happened before. ‘Early producers couldn’t reference the genre – they had outside influences and outside genres they used.’ Following Dizzee Rascal’s Boy in Da Corner, Mitch argues, grime became more formulaic with producers sticking to 140bpm: ‘It is weird how that album was really quite experimental. That album had tempos all over the place and sounds in weird places.’ Grime’s messy origins seem to have been rediscovered only recently.

Mitch’s pitched down, spacious remakes are baffles amid the intensity of grime sets. His sets begin like seizures. Mitch understands – I’ve seen him glancing, measuring up the dance floor – how the energy drain might be as intensely felt as the famous energy flash. His contrasts pronounce the dispersion of one kind of intensity for another: when it begins the body is still moving with the physical memory of the previous set – a frenetic, warm-down bob. You become aware of listening, of other people’s conversations taking place all around you. Like when the lights come on at the end of the night. For Mitch, it’s all about the vibe. He sculpts it with tenacity.

‘Nostalgia,’ Svetlana Boym has written, ‘is a sentiment of loss and displacement, but it is also a romance with one’s own fantasy.’ Nostalgia comes from the Greek roots nostos meaning ‘return home’ and algia meaning ‘longing’. Why is music always charged with transporting us to far-flung places? If music exists in the moment of its listening, samples, envelopes of affects, deliver the past to us now, for today. Mitch’s Blackstreet sample doesn’t arrive intact because today love songs are different. Emotion is different. With Mitch, nostalgia is just the hook that stages how things are different. And although delicate, his ‘Don’t Leave’ fills the ears by force, soon erasing any residual memory of Blackstreet’s verse or chorus, overdubbing nostalgic longing. In this way he pushes longing into the future, makes an optimistic thing of it.

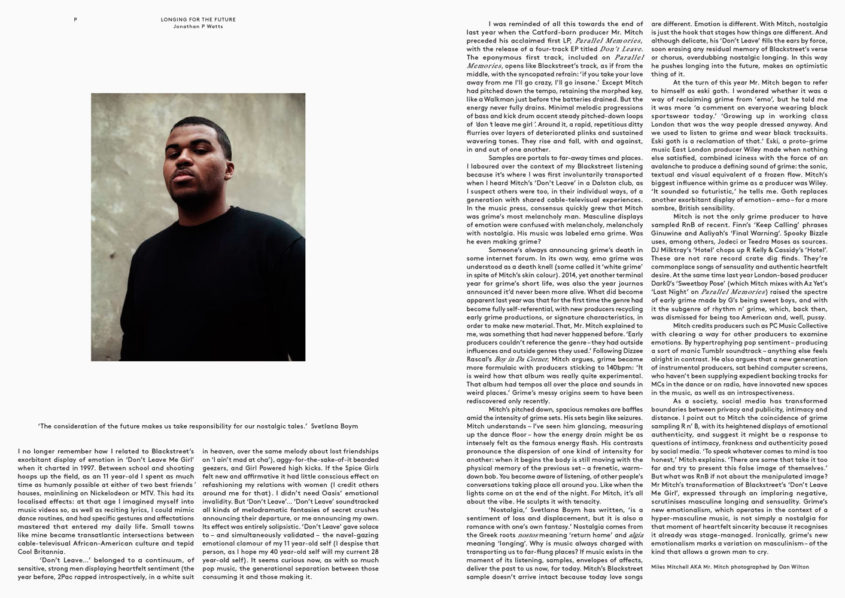

At the turn of this year Mr. Mitch began to refer to himself as eski goth. I wondered whether it was a way of reclaiming grime from ‘emo’, but he told me it was more ‘a comment on everyone wearing black sportswear today.’ ‘Growing up in working class London that was the way people dressed anyway. And we used to listen to grime and wear black tracksuits. Eski goth is a reclamation of that.’ Eski, a proto-grime music East London producer Wiley made when nothing else satisfied, combined iciness with the force of an avalanche to produce a defining sound of grime: the sonic, textual and visual equivalent of a frozen flow. Mitch’s biggest influence within grime as a producer was Wiley. ‘It sounded so futuristic,’ he tells me. Goth replaces another exorbitant display of emotion – emo – for a more sombre, British sensibility.

Mitch is not the only grime producer to have sampled R n’ B of recent. Finn’s ‘Keep Calling’ phrases Ginuwine and Aaliyah’s ‘Final Warning’. Spooky Bizzle uses, among others, Jodeci or Teedra Moses as sources. DJ Milktray’s ‘Hotel’ chops up R Kelly & Cassidy’s ‘Hotel’. These are not rare record crate dig finds. They’re commonplace songs of sensuality and authentic heartfelt desire. At the same time last year London-based producer Dark0’s ‘Sweetboy Pose’ (which Mitch mixes with Az Yet’s ‘Last Night’ on Parallel Memories) raised the spectre of early grime made by G’s being sweet boys, and with it the subgenre of rhythm n’ grime, which, back then, was dismissed for being too American and, well, pussy.

Mitch credits producers such as PC Music Collective with clearing a way for other producers to examine emotions. By hypertrophying pop sentiment – producing a sort of manic Tumblr soundtrack – anything else feels alright in contrast. He also argues that a new generation of instrumental producers, sat behind computer screens, who haven’t been supplying expedient backing tracks for MCs in the dance or on radio, have innovated new spaces in the music, as well as an introspectiveness. (Mitch’s label, Gobstopper, is the go-to for innovative new music.)

As a society, social media has transformed boundaries between privacy and publicity, intimacy and distance. I point out to Mitch the coincidence of grime sampling R n’ B, with its heightened displays of emotional authenticity, and suggest it might be a response to questions of intimacy, frankness and authenticity posed by social media. ‘To speak whatever comes to mind is too honest,’ Mitch explains. ‘There are some that take it too far and try to present this false image of themselves.’ But what was R n’ B if not about the manipulated image? Mr Mitch’s transformation of Blackstreet’s ‘Don’t Leave Me Girl’, expressed through an imploring negative, scrutinises masculine longing and sensuality. Grime’s new emotionalism, which operates in the context of a hyper-masculine music, is not simply a nostalgia for that moment of heartfelt sincerity because it recognises it already was stage-managed. Ironically, grime’s new emotionalism marks a variation on masculinism – of the kind that allows a grown man to cry.