‘We need a lighthouse philosopher,’ suggests Roque Pina, the protagonist of Filipa César & Louis Henderson’s captivating essay-film Sunstone, 2017. Though you would be forgiven for thinking that Pina already fulfils this role as he flatly, matter-of-factly addresses the origins of the lighthouse, its development and future, and reveals its inextricable relations with Enlightenment epistemologies, piracy, optics, colonialism, the military-industrial complex and workers’ rights. Pina’s philosophy is based in practice: he alone is keeper of Cabo da Rosa, a lighthouse situated at the westernmost reach of continental Europe on the Portuguese coast.

Beneath the lighthouse, amid the din of international tourists, the film shows the words, translated, of the 16th-century poet Luís de Camões chiselled into stone: ‘Here … / Where the Earth ends / And the sea begins.’ Once considered a terrestrial limit, it situates Cabo da Rosa as a frontier of seafaring navigation and conquest of a (recently proven) spherical Earth – a primal scene of global commodity exchange. When pirates operated lighthouses they used them to wreck and rob ships. Monks used them to aid navigation. Whatever their intentions, both aspired to illumined legibility in archaic forms of mercantile communications. Light in Sunstone emerges as a material substrate of various intersections of navigation and legibility in contemporary image-based communications capitalism. Only a materialist analysis of light, which the film proposes and advances, could account for its actions.

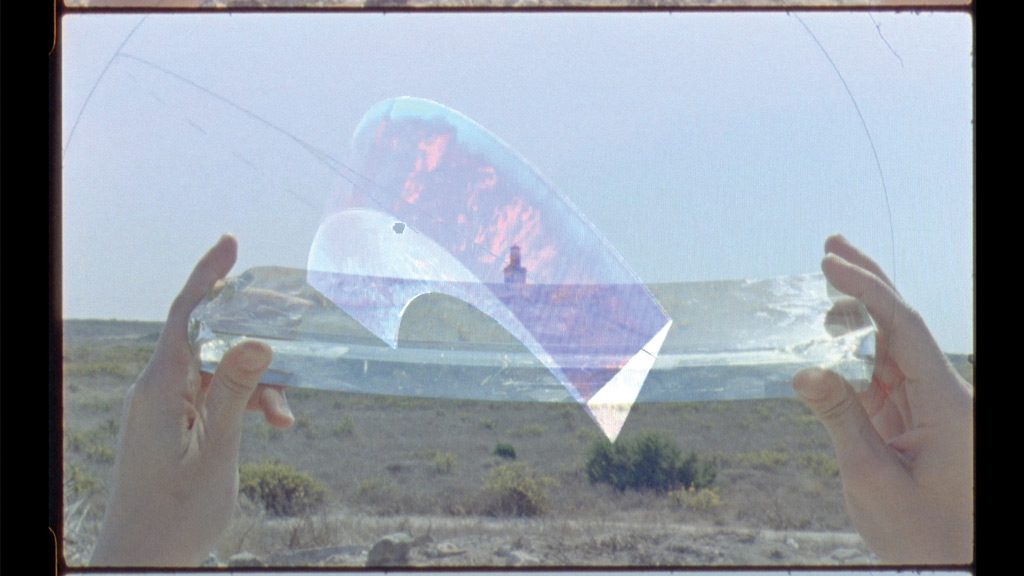

Isn’t a materialist analysis of immaterial light folly? As a spherical lens is held up to the light of the Atlantic for examination (a visual reference, perhaps, to Jean Epstein’s Termaji, 1952), Pina cautions the viewer: ‘Through words we can’t really perceive the propagation of light.’ César and Henderson, combining 16mm analogue film and CGI, remind us that cinema is uniquely placed to carry out this materialist analysis. Sunstone is, therefore, also a film about the cinema’s apparatus. By refashioning the convex spherical lens into a series of concentric annular sections, the French physician Augustin-Jean Fresnel invented a lens that, placed in front of a light source, could refract and concentrate a beam of light more powerful than ever before. Because it required less material it was cheaper to produce and much lighter so larger lenses could be housed in the lantern. Throughout Sunstone, the appearance of Fresnel lenses in Cabo da Rosa, in museums or as fragments held up to the light become ciphers for the architecture of the movie camera itself – the lens pointing at the lens pointing at language’s limits.

Accompanied by Pina’s voice-over, Sunstone collages César and Henderson’s 16mm film with appropriated YouTube footage – amongst other things, of satellites, cartographies and a GoPro on a Hammerhead shark, sections from the filmmaker Chris Marker’s Sans Soleil, 1983, archival film by the Cuban filmmaker Santiago Álvarez and data visualisations of the ‘infosphere’ from the ‘Architecture of Radio’ app designed by Richard Vijgen. Ranging from the terrestrial via the submarine to outerspace, penetrated as if stratified surfaces by the camera’s point-of-view, these multi-format moving images, produced by humans, animals and machines, demonstrate an omnipresent virtuosity of visuality. If César and Henderson’s 16mm celluloid film bears indexical images, the digital, we are shown, is an array of codes that produces computational images of things in the world. The artists’ frequent overlay of screen captures from Vijgen’s infosphere app with striated CGI meshes or 16mm film, producing dense, sometimes illegible, Baroque imagery, shows how the invisible is central to a new regime of visuality: visualisations are translations that express things beyond the spectrum of light and human perception. Yet the network (flat, enmeshing the sphere) consists of fibre-optic cables constructed of thin glass rods. Agencies – machine, human, animal – and ownership – corporate, public, military – are obscured. As Pina reminds us, ‘all technological advancement is connected to the military’.

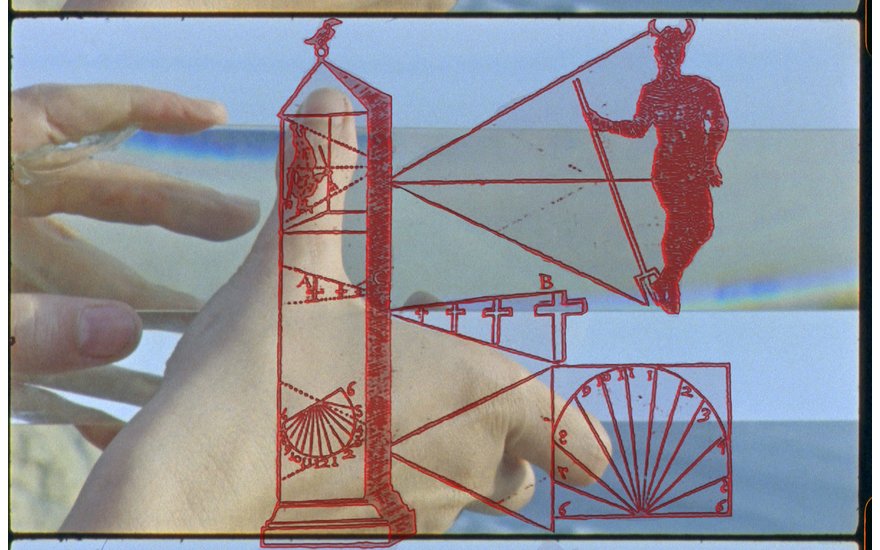

There is a profound moment in Sunstone where the far-reaching implications of a counter-history to transparency begin to form. Symptomatic of changing global communications, lighthouses, Pina explains, were installed with differential GPS transmitters first used by the US military and then by commercial airlines. When 9/11 occurred, the US government switched off GPS to throw any further weaponised aircraft off course. ‘The whole world,’ Pina says, inverting the Christian edict, ‘was thrown into darkness.’ Opacity, in this instance informational, is put into operation against terrorism. By including a diagram from the French-Caribbean writer Édouard Glissant’s 1990 book Poetics of Relation, César and Henderson invoke his philosophy of opacity (increasingly influential among contemporary artists and curators, from Zach Blas to Metahaven, Trevor Paglen to Renate Lorenz and Pauline Boudry, Shama Khanna to Nkisi), which he argues as a human right. ‘If we examine the process of “understanding” people and ideas from the perspective of western thought,’ Glissant writes, ‘we discover that its basis is this requirement for transparency.’ Elsewhere, he argued that ‘to acclaim the right to opacity … is to establish that the inextricable, planted in the obscure, also drives clarities that are not imperative’.

The ‘Op’ of the exhibition title, ‘Op-Film’, is, among other things, an allusion to the pioneering filmmaker Harun Farocki’s formulation of the ‘operational image’ – a calculable image that is used to ‘do’ things, that have a specific function. Sunstone, though avowedly indebted to Farocki’s method, extends his preoccupations into novel territories. César and Henderson’s film is that of cineastes. And of researchers and intellectuals. Accompanying the installation at Gasworks was an illumined shelf with lens fragments and three vitrines displaying texts, diagrams, maps and lenses encountered during research. The carefully curated display is what subtends a complex film, that, as Pina warns, emphasises language’s limitations, a non-didactic visual materialist film-as-philosophy. In our age of the ubiquitous calculable image there is an imperative to withhold while reproducing conditions of possibility.