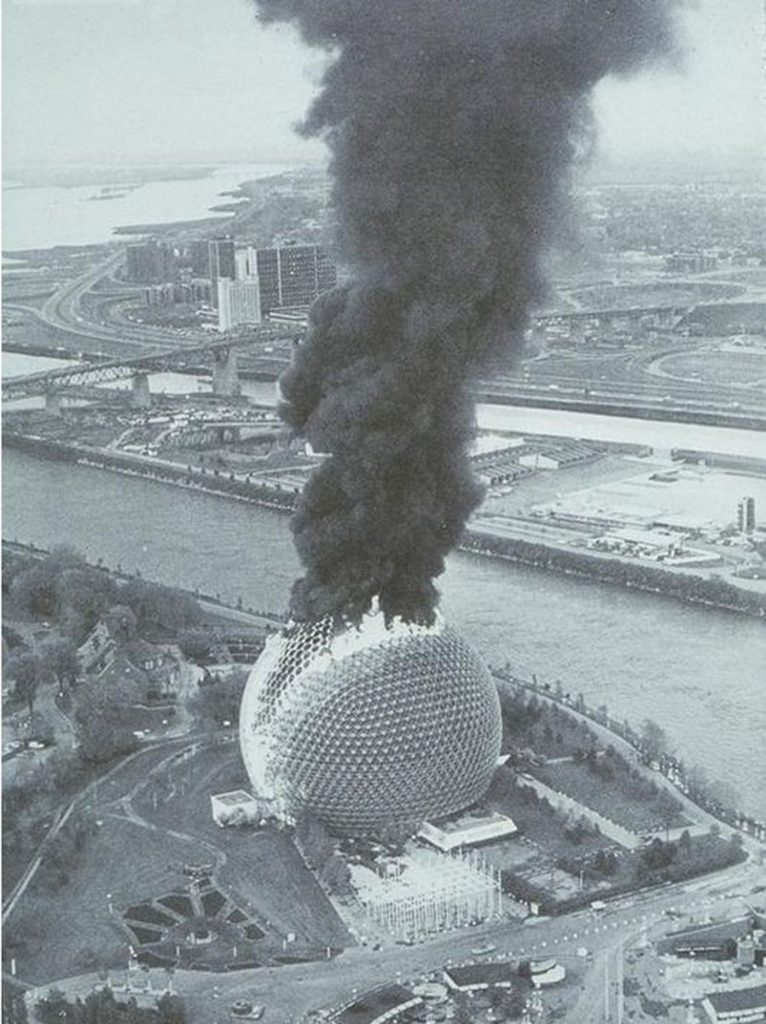

Few images conjure techno-modern utopia’s discontents like Buckminster Fuller’s Montreal ‘Expo 67’ biosphere in flames. Lit by a welder’s spark during structural renovation in 1976, the acrylic carapace of the icosahedron dome burnt fiercely for 30 minutes before extinguishing. Probably the lean efficiency of Fuller’s structures – he converted, as the critic Martin Pawley nicely put it, the Bauhaus epigram ‘Less is more’ to ‘More for less’ – prevented a conflagration.

In a booth at the entrance to ‘Floating Worlds’ at the Sucrière, one of three venues of this year’s Lyon Biennale – curated by Emma Lavigne – Julien Discrit’s fine film, 67_76 (2017), explores the allegorical richness of this image. Excerpts from Fuller’s survivalist handbook for the Age of Aquarius, Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth (1968), narrate Discrit’s sun-kissed film, shot in shallow depth-of-field focus, featuring sexy, free youth in the kind of ‘one life live it’ television adverts Facebook makes to sell alienated connectedness: ‘Our sun is flying in company with us, within the vast reaches of the Galactic system, at just the right distance to give us enough radiation to keep us alive, yet not close enough to burn us up.’

Opposite the entrance, a dirge at the end of Discrit’s parenthesis, is Bruce Conner’s Crossroads (1976), a chillingly impersonal sequence of 24 declassified US army films documenting nuclear tests off Bikini Atoll. ‘THE END,’ reads the tombstone-like closing credits, as though Conner believed it really was – despite the fact that we’re viewing it on loop. In a biennale that, with few exceptions – Khadim Ali’s ‘The Arrival Series’ (2017) at the Institut d’Art Contemporain – barely speaks to the violence and confusion of contemporary life, the current nuclear standoff between North America and North Korea could be seen as a propitious gift activating Conner’s film. A biennale is not the news.

Why the preponderance of geodesic domes? Throughout the biennale, there are at least six. Lavigne, who is director of the Centre Pompidou-Metz, France, even brought a ribbed fibreglass specimen from her home institution. Installed in the Place Antonin Poncet in the centre of Lyon it temporarily houses the sound artist Céleste Boursier-Mougenet’s installation clinamen V4 (2017). Inside, floating in a wide shallow pool, 40 variously sized white ceramic bowls swirl and chink with a diametrical flow produced beneath the surface, the dome’s boomy acoustics dispersing the fluid indeterminate composition. Where artists such as Mary Mattingly or Tomás Saraceno have recently revisited geodesic domes as alternative structures in the face of ecological catastrophe or as spaces for exchange, Boursier-Mougenet’s installation is an enclosed space, guarded by security, in a public square that offers Zen-like beauty and meditation. If it articulates a cultural world of Black Mountain College – where Fuller taught with John Cage and others – it does little to update it. What image of modernist utopia is evoked here?

This is the problem, too, with the pat, reverential museum exhibition of 44 artists across three floors at Musée d’Art Contemporain (MACLyon). MAC is, after all, a museum, and the biennale seeks to explore ‘the legacy and scope of the concept of modernity’. But this hackneyed narrative begins with various bunched-up works by Marcel Duchamp, takes in Jean Arp and Alexander Calder and situates Lucio Fontana’s pierced and slashed Concetto Spaziale (spatial concept) canvases as an interesting overlooked moment. Lavigne does little to reframe a well-rehearsed narrative of modernity’s history, only to pull other works into its Eurocentric vortex. Because the vortex is ocularcentric the presence of sound art – for example David Tudor’s wonderful Rainforest V (variation 2) (1973/2015) – feels fetishized, as though the sonic were always outside of modernity’s sensations, when actually it was marginalized by visual art’s institutions. Incorporating it in a gallery disciplines it to the rule of the visual, as poignantly illustrated by the display of scores by Philip Corner and Terry Riley.

At the Sucrière, the most compelling works of 41, mostly European and American, artists comprises of, or incorporates, the sonic. Following a composed score, nine high rigged taps in Doug Aitken’s Sonic Fountain II (2013–17) drip onto an amplified pool beneath. Tomás Saraceno’s installation Hyperweb of the Present (2017) – the highlight of the biennale – displays a large spider in its web beneath a spotlight: as it goes about its labour of spinning, two very fine contact microphones amplify its complex, tensile structure.

Aside from Fontana’s production of four-dimensional space (Fuller wrote books on the fourth dimension in the 1920s), Lavigne cites as her inspiration for ‘Floating Worlds’ Umberto Eco’s writing of the early 1960s on ‘the open work’, which situated the spectator as co-producer of artistic works. Likewise, Zygmunt Bauman’s idea of ‘liquid modernity’ enabled her to think of melting and reforming modernity. These are ideas of plurality, ambiguity, openness and instability. At ‘Floating Worlds’ they’re a conceptual foil for nebulous poetry. Fear and anxiety is left at the door. I’m reminded of something the choreographer Yvonne Rainer wrote about John Cage’s ‘goofy naiveté’ in 1981: ‘We must awaken to the ways in which we have been led to believe that this life is so excellent, just, and right’.