Several days after our arrival in Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC) – I was travelling with my sister, brother and cousin – the Vietnamese Defence Minister, General Ngô Xuân, received US Defence Secretary Jim Mattis for closed-door talks on a $183m clean-up operation of nearby Biên Hòa airport. A little more than an hour’s drive north-east of the capital, Biên Hòa was used by the US during the Vietnam war to store vast quantities of Agent Orange, the toxic chemical defoliant approved by President Kennedy for destroying the jungle canopy to reveal enemy supply lines, often routed through tunnels.

Its effects on humans and the environment was, and continues to be, devastating: according to the Vietnamese Association of Victims of Agent Orange, since its first use in 1961 three million people across several generations have been affected by related diseases, including cancers, neurological disorders and birth defects. Biên Hòa remains one of the most polluted sites in the country. Forty years after US forces withdrew from South Vietnam, Mattis was there, or so he told the press, ‘to show the support of the Defence Department for this project and demonstrate that the United States makes good on its promises’.

I feel conflicted about opening my report like this, reiterating a trauma within living memory that for many Europeans is the horizon of their mediatised knowledge of a country with an extraordinarily complex past. But Xuân and Mattis’s meeting does speak to colonial legacies in a post-communist society that since the implementation of Đổi Mới (open door) economic reforms in 1986 – coincident with the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachov’s ‘Perestroika’ glasnost (‘openness’) economic reforms – has rapidly transformed in the global free-market.

Tourism – particularly dark tourism – is a facet of this. For example, those I know who had previously visited HCMC recommended, without exception, The War Remnants Museum (formerly the Museum of Chinese and American War Crimes) and the Củ Chi tunnels, a sprawling network of tunnels used by communist soldiers as communications and supply routes north of the city. Today, some of the tunnels have been expanded to accommodate western tourists; here, tourists can fire an authentic Soviet AK-47, a dollar a pop.

I already knew about the tunnels because of The Propellor Group’s dual-screen video installation The Guerrillas of Củ Chi, 2012. One screen, showing a 1963 Viet Cong propaganda film profiling Yank-killing heroes, faces up to another screen with an image that aligns with targets at the end of the range. Tourists pay, lock and load, aim and fire, figuratively, at the guerillas. In 2011, The Propellor Group rebranded communism for the 21st century. Their Viet Nam The World Tour, 2010-, is, in their words, ‘a rogue anti-nation-rebranding campaign … [to] re-associate a historically colonised and mediated national identity with an entirely new mediated history’.

Based between California and HCMC, The Propellor Group consists of American-born Matt Lucero, and Phunam and Tuấn Andrew Nguyễn, who were born in Vietnam but grew up elsewhere, Phunam in Singapore and Nguyễn in the US as a war refugee evacuated from the North. Such refugees are known, apparently, as ‘the boat people’ and overseas Vietnamese go by the name ‘Việt Kiều’, a label not without judgment from the nationalist state, that translates as something like ‘Vietnamese sojourner’.

It’s the so-called sojourners who are the most well-known on a global art stage and who produce – who have the privilege to produce – interrogative work about a country where the state cultural police still show up at exhibitions to cover works with brown paper bags. Trinh T Minh-Ha has exhibited in major biennales; Dinh Q Lê had a solo show at MoMA in 2010. Indeed, as the pioneering historian of contemporary Vietnamese art Nora A Taylor writes in an article titled ‘Đổi Mới and the Globalisation of Vietnamese Art’, co-authored with Pamela N Corey, ‘If one is to think “Vietnam” through contemporary art, it is thus no surprise that the most internationally renowned artists within the last two decades have largely been Vietnamese-American … due to the imbrication of their work in discourses of migration, historical memory, and identity, and the conceptually sophisticated presentation of their work honed through postgraduate art education in the United States’.

When Taylor began researching what would become the 2009 book Painters in Hanoi, beginning with the formation of the French colonial art school, École des Beaux-arts de l’Indochine, in Hanoi in 1925 and running through to post-reunification a socialist-oriented market economy, she soon realised the need for an ethnographic approach because, she writes, ‘Although alive and well in artists’ studios, there was little Vietnamese art to be found in museums and archives. A luxury item in the view of a government with little cash available for preservation, conservation, and documentation, art and its history existed through people’. In a country where until 1986 it was illegal to exhibit nudes and abstract art, any art that was ‘modern’ had to be made and shared covertly in private homes (Salon Natasha, opened in 1990 in Hanoi, is a fascinating instance of such an underground community).

It was the artist Sung Tieu, a recent Royal Academy Schools graduate, based between Berlin and London, who suggested a few galleries I might visit: in Ho Chi Minh City, MOT+++, Sàn Art, A.Farm (a residency initiated by the previous two and Nguyen Art Foundation), The Factory (run by the Australian Zoe Butt, former director of Sàn Art, co-curator of the upcoming Sharjah Biennial 14) and Galerie Quỳnh; in Huè, Cafe Then and New Arts Space Foundation (founded by artist-duo Le Brothers); and in Hanoi, Six Space, Manzi Cafe, A Space, Heritage Space and Nhà Sàn Collective (an artist-led organisation founded in 1998 to support exhibitions, education and exchanges). Temporary artist-led spaces pop up and disappear again, registering activity online with Instagram profiles or Facebook pages, Sung told me.

Although Galerie Quỳnh’s current location is recent, in a beautifully renovated former Korean cookie store in Dakao, District 1, it has been a fixture in the city for nearly two decades. Established by Quỳnh Phạm in 2003 – like Tuấn Andrew Nguyễn, a war refugee relocated to the US where she was educated at the University of California and the Smithsonian Institute, and held positions at, amongst other organisations, the Museum of Contemporary Art in San Diego before returning to Vietnam – the gallery runs a regular programme of represented artists. In the absence of public funding for the arts, Phạm has raised income from sales and supporters, and collaborated with other spaces in the city, to run a public education programme and produce bilingual (Vietnamese and English) publications with scholarly texts.

In 2014, the gallery launched Sao La, a short-lived non-profit initiative in the grounds of the HCMC Fine Art Museum co-curated with two young artists, Tung Man and Nguyễn Kim Tố Lan, as a platform for contemporary art exhibitions, screenings, workshops and lectures. Briefly, it became the spot for local and visiting artists and architects, but was closed because, Phạm explained, ‘learning and education does not align with what the Museum does’. ‘The authorities don’t understand the idea of a not-for-profit,’ she continued, ‘but a commercial gallery makes sense, so they leave me alone.’ Later this summer, a group show of young Vietnamese artists that Phạm advised on, titled ‘Where The Sea Remembers’, will open at The Mistake Room in Los Angeles.

During my visit the artist UuDam Tran Nguyen was busy installing his first solo show with the gallery, ‘Serpents’ Tails’, at the centre of which a vast tangle of stitched plastic bags inflated by motorcycle exhausts cascaded across the gallery’s four floors and out onto its fascia. Clearly a meeting point for artists and curators in the city, as UuDam showed me his work, Nhung Walsh, director of Indochina Arts Partnership dropped in. Yoko, another friend who was helping with the installation, had to leave to open up Yoko Bar, her live music venue and event space.

Mixed programmes of exhibitions, workshops, education and residencies is characteristic of HCMC’s leading critical contemporary art spaces, such as the artist-led non-profit space Sàn Art, co-founded by Dinh Q Lê. This is also the model for the non-profit artist-led space MOT+++. Principally a low-key gallery space with an exhibition programme, the organisation is run by an international collective that also hosts an experimental sound art project, bills itself as a ‘museum by any other name’ that places a single art work for a year in a chosen location throughout the world, keeps a small art library open to the public, and manages the A.Farm residency for international and Vietnamese artists. One of the founders, artist Cam Xanh – although I’m told by a member of the collective that they don’t speak of founders as such – also co-founded the Nguyen Art Foundation in 2018 with Quynh Nguyen to ‘build an alternative infrastructure for the arts in Vietnam from its base of Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon), and lay the base for what it hopes will form Vietnam’s first museum of contemporary art’. Housed between HCMC and Geneva, Postvidai is another private collection of contemporary Vietnamese art: because of the absence of public institutions, private patronage plays a significant role.

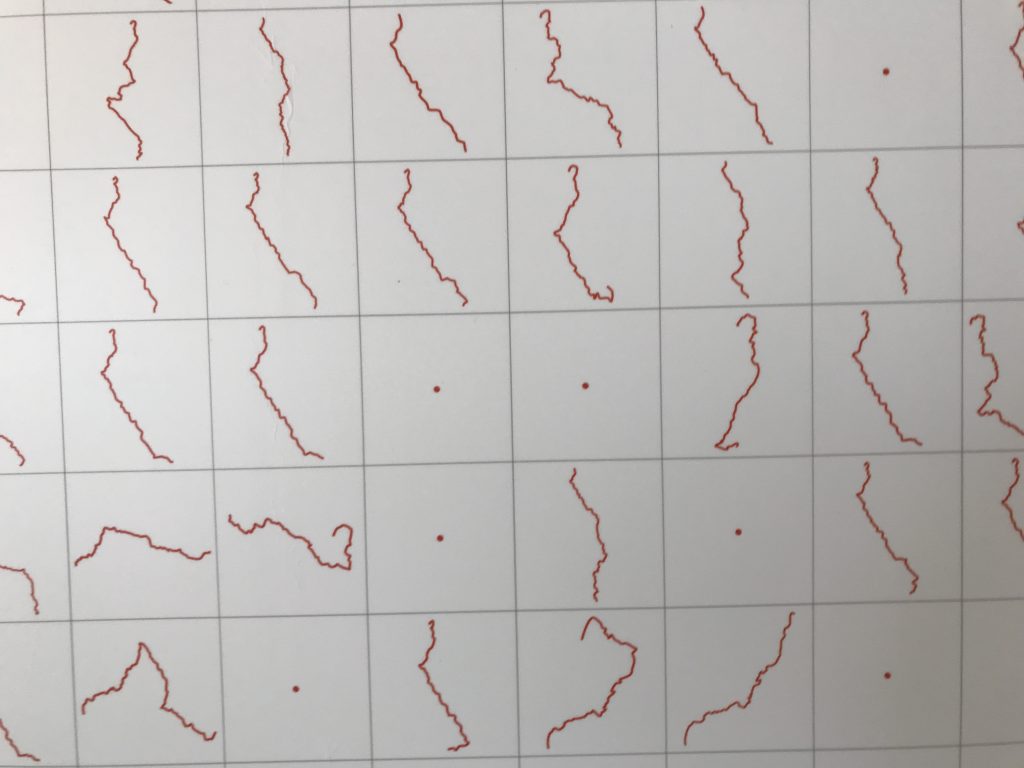

At MOT+++, Kim Duy, a young artist and collective member who helped install the current exhibition by Phùng Tiến Sơn, on learning that I was from the UK asked whether I knew Sung Tieu – they had met in Germany while he was doing post-graduate studies. ‘Sung brought me here!’ I laugh, astonished to find such familiarity. Sơn’s installation Soundtracks, Duy tells me in English, plotted 1,768 routes taken by Vietnamese soldiers from their homes to Vi Xuyen National Martyrs’ Cemetery in North Vietnam. All of them had died in a brief border skirmish with imperial China in 1984. Sơn did not learn about this anti-colonial conflict in school. His series of line drawings, arranged in a grid, plot the sinuous routes taken to a martyr’s grave for a conflict that never happened.